Finance

[Exclusive] Korean investors' $16.8b coal exposure highlights call for climate action

|

Steam rises from the five brown coal-fired power units of RWE, one of Europe‘s biggest electricity companies in Neurath, northwest of Cologne, Germany, March 12, 2019. RWE is one of the companies to appear on the Global Coal Exit List by Germany-based nonprofit organization Urgewald. (Reuters-Yonhap) |

Forty South Korean investors were found to have invested a total of $16.8 billion in securities issued by thermal coal-related companies worldwide as of January, data exclusively obtained by The Korea Herald showed Feb. 25.

The figure highlights calls for more aggressive climate action on the part of the investors, beyond just declaring an end to additional coal investing, for a nation that pledged to achieve carbon neutrality by cutting emissions to net zero by 2050 for a more sustainable future.

Korea was home to institutional investors with the ninth-largest coal exposure combined in the world, which accounted for 1.6 percent of global coal exposure, according to data from German-based nonprofit organization Urgewald and research firm Profund. The total investment was fourth largest in Asia, following Japan, India and China.

The institutions, including the world’s third-largest pension fund the National Pension Service, were found to be holding either stocks or bonds of 147 companies at home and abroad associated with the coal power supply chain.

Urgewald defines coal-related companies in its Global Coal Exit List as those in either mining, producing power, providing energy services or utilities with a coal share of revenue of 20 percent or more.

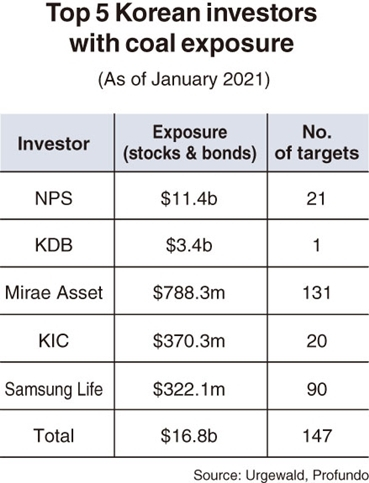

According to Urgewald’s data, NPS’ coal exposure through stocks and bonds in 21 companies came to $11.4 billion, 11th most in the world. This was followed by state-run lender Korea Development Bank‘s $3.4 billion exposure, Mirae Asset Financial Group’s $788.3 million exposure, sovereign wealth fund‘s $370.3 million investment and Samsung Life Insurance’s $322.1 million.

The finding indicated that nearly 70 percent of Koreans‘ total coal investment went to Korea Electric Power Corp., a state-run utility provider. Kepco last year was under fire from international investors for its involvement in Vung Ang 2, a coal-fired power plant project in northern Vietnam.

They were investing in not only Korean companies such as Kepco and steelmaker Posco, but also overseas companies including India-based Larsen & Toubro and Power Finance, as well as US-based Duke Energy, Ameren and Air Products & Chemicals.

In the meantime, Korean banking services firms extended $5.8 billion in loans to GCEL companies and underwrote their issuance of shares or bonds worth $7.9 billion from October 2018 to October 2020, data also showed. Twenty-one companies on the GCEL were able to get financing from Korean capital.

By company, NongHyup Financial Group provided either loans or underwriting services worth a combined $3.8 billion, followed by KDB’s $2.2 billion, the state-run Export-Import Bank of Korea‘s $1.6 billion, Kyobo Life Insurance’s $1 billion and Mirae Asset Financial Group‘s $753 million. Their financial services also focused on Korean firms such as Kepco and Posco.

|

Earlier in October, the Moon Jae-in administration declared a net-zero emission goal by 2050. This triggered local financial institutions’ respective pledges to refrain from further coal investing and financing. Banking group KB Financial Group in October declared an end to additional coal-related financing, and local peers Woori, NongHyup and JB followed suit. Chaebol-owned financial affiliates of Samsung and Hanwha also joined the bandwagon.

But a divestment from coal-related holdings is a more viable signal than a pledge to stop coal investment, said Youn Se-jong, director of Seoul-based NGO Solution for Our Climate.

According to Youn, divestment from the coal power supply chain is practically the only way to sever a vicious cycle where coal-fired electricity producers and distributors attract investment at low financing costs, maintain their coal-related business and continue to emit greenhouse gas.

“We are seeing a continuous demand to keep coal-related businesses afloat,” Youn told The Korea Herald. “Institutional investors‘ action to cut coal exposure will lead to a trickle-down effect under which coal-related companies must bear a higher financing cost.”

Moreover, the Korean financial industry has yet to fully perceive coal as a losing investment strategy, according to Hong Jong-ho, professor of Economics at the Graduate School of Environmental Studies at Seoul National University.

“We are seeing a gap between the government‘s coal phase-out goals and the reality,” Hong told The Korea Herald.

“Ironically, coal investing does not appear to be unattractive yet, considering how coal-fired electricity is being priced in Korea. But we will eventually see a turning point in the near future where things suddenly change.”

This is aligned with the findings of Urgewald, Reclaim Finance, Rainforest Action Network, 350.org Japan and 25 further NGO partners, announced Feb. 25, that 4,488 institutional investors held $1.03 trillion worth of stocks or bonds in such companies.

Of the total, 58 percent of investments came from US-domiciled investors, including Vanguard and BlackRock, showing a contrast from European investors who have begun screening coal companies out of their portfolios.

The report also urged Korea’s neighbors to take stern actions, calling Japanese financial companies “top lenders” and Chinese peers “top underwriters” of financing by the global coal-related companies.

“Our research underscores how dire the consequences of this failure are,” said Katrin Ganswindt, head of financial research at Urgewald. “If we do not move financial actors in the US, Japan, China, the UK and other key countries to exit coal soon, they will propel us into a future where the Paris climate goals are no longer within reach.”

By Son Ji-hyoung (consnow@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How LG Energy Solution’s bold bet paid off with Tesla, Mercedes deals](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=151&simg=/content/image/2024/10/29/20241029050614_0.jpg)